Diary of a Dash Across Australia

- Chris Wright

- Oct 4, 2019

- 18 min read

So it was like this.

I got a message from my friend Heath, who was on his way from Busselton in Western Australia to Gold Coast in Queensland, a cool 5,000km or so, to collect a boat and bring it all the way back home again.

But on the way there, he found he would have to fly home to attend to business at his restaurant.

So how would I feel about flying down to Gold Coast to split the drive home with his wife, Melina, with two of their children, Sailor and West, in the back? It would only take five days, the whole width of Australia, including the Nullarbor. So…

WEDNESDAY

Gold Coast, Queensland to Lightning Ridge, New South Wales

My overnight budget flight from Singapore lands in Gold Coast at 7.40am. On the way in, the Pacific Ocean has filled the window; it is the first of three oceans I will see in the next five days.

Customs is quick today and I’m out the front with a coffee by 8.30 to see a Land Cruiser with a tin boat on a trailer attached to the back, doing laps in the airport carpark. (This is lap six, it turns out.) In it are Melina, Sailor and West. Melina pauses long enough for me to chuck my bag in the back, and with that, we’re on the road.

The first hour or so is dull highway up towards Brisbane before we head to the interior. The ads on the billboards and radio as we roll into green pastoral land are the first clue that we’ve left the city, as farm equipment and bull semen adverts take their place alongside those for cars and booze. Brown cows roam the fields as we approach Gatton, and everything seems to have Lockyer in its name.

When we reach Toowoomba I take the wheel for the first time and get used to the heft of the Land Cruiser and the drag of the boat. I haven’t driven anything with a trailer since I was 19 but I decide not to mention it until someone asks, which takes a further four days, by which time there’s not much to be done about it.

We move into flood plains where billboards saying “Got a brain? Move the train” appear against stacks showing the height they say a new railway needs to be to in order to avoid flooding. We drive past the Big Orange, which is quite a modest orange in truth, then the Big Elephant, which is notably smaller than an actual elephant.

West, 14, is thrilled at the whole adventure. “I’ve got an axe,” he says.

He announces his plan, sooner or later, to build a fire and make damper.

“What do you need for damper?” asks Sailor.

“Flour and water.”

“That makes glue,” says Sailor.

Melina takes the wheel again. The greens and yellows of hills and Queensland farmland turn redder as the dirt becomes the Outback. Stately gums are replaced by scrub and scrawny blackened fire-scorched trunks and featureless thorn bird boughs. Pubs ever more remote appear, with humour attached. “Free beer,” says the Nindagilly Pub, “….yesterday.”

In Thallon, Queensland, the grain elevators have been painted in a vivid bush mural. Late in the day we cross to New South Wales, whose first greeting is a sign warning about speeding. And before dark we reach Lightning Ridge, a town built on opal mining where many of the pubs and homes are built underground to escape the heat.

The campground is surprisingly busy for a place that seems so remote. Sophisticated, too: it has a pristine pizza oven and toilets you could eat off the floor of. We cook burgers on the free gas barbecues and compete to get them cleaner than anyone else does.

My friends have got me a swag. I was never entirely clear about what a swag actually is. It’s like a mini-tent, something you can lie down in but nothing more; you put a sleeping bag in it, climb aboard, zip yourself in to the thing and shut out the world. In the morning you roll it all up with the sleeping bag still inside, strap it tight, put it in a bag, chuck it in the Land Cruiser and off you go.

I am completely sold on swags. I sleep better in them than I do at home, the outside world totally shut out, like I’m put on standby. They are so simple but effective.

That evening we wander across the road to a hot spring – and hot it most certainly is. It turns out to be sitting on top of an artesian well the size of one fifth of Australia. It is packed. An artesian well spa in the absolute middle of nowhere in a New South Wales opal mining town is packed. Truly, there is a whole world happening in Australia’s interior most of us know nothing about.

THURSDAY: Lightning Ridge, NSW – Broken Hill, NSW

We’re up with the sun. Melina makes coffee on the back of the Land Cruiser and we begin a routine of stacking down tents and swags and West mooring them onto the roof rack and into the boat.

Today I take the morning drive and quickly make a mistake. I’ve been warned about driving at dawn because of the wildlife. You see it heaped dead in the road: mostly kangaroos and emus, broken and bent on the asphalt. Melina has warned me that if a roo jumps out in front of you you don’t try to avoid it but go straight into it and let the roo bars take the impact. But when one jumps out I’m distracted by a car further up the road. I hit the brakes and instinctively pull the wheel. It works out fine – miss the roo, keep control of the car, the trailer doesn’t jackknife – but I’m rattled.

Gradually I understand the hierarchy of stupid wildlife. Kangaroos are morons. They will look right at your speeding car and then jump in front of it. Emus are scarcely better, vaulting fences at a mighty speed and careering in their ungainly way as if they ought to have arms for balance but have somehow misplaced them. Sheep, not especially smart; but goats, you don’t see them dead, because they have the common sense not to leap in front of the car. Disappointingly I take out a bird as well, which we think might now be wedged in the roof rack.

It will be the biggest challenge of the trip, though, especially at dusk. Melina’s eyesight is better than mine, but more to the point she has decades of experience of spotting the shade of beige, amid a million other shades of beige in a darkening roadside, that constitutes not bush or dirt but a kangaroo ready to jump. I don’t. Soon I assume everything is going to jump. I slow down for rocks, bushes, tyres, sometimes for what turns out to be the road itself.

We are among farms again as we head south towards Nyngan – crossing, I’m delighted to learn, the river Bogan – before turning due west for hundreds and hundreds of kilometres. It’s mostly still pastoral here, or dusty brown land, big gums on the roadside. (As a rule of thumb, whenever I ask what a tree is, I’m told it’s a gum. I think Australians are winging it actually.) Cattle, sheep, and tyres everywhere, piles of tyres, used as markers, wrapped around signs, stacked outside farms.

We are, quite literally, out the back of Burke, spending hundreds of dollars a time in three or four Caltexes a day, bouncing over cattle grids and skirting massive agricultural equipment on trucks with escorts before and behind them, West chatting away to truck drivers on the CB radio.

I try to master the etiquette of waving. It goes sort of like this. The more remote the road and the lighter the traffic, the more likely you are to wave at a passing motorist. You always wave at someone towing a caravan. Trucks, more of a grey area. But what to go for? The bold salutation? The cursory nod? I settle upon raising a few fingers from the wheel while keeping a thumb on it, enough to acknowledge without getting all emotional about it. If someone doesn’t wave back I can simmer about it for several hundred kilometres. If I fail to wave at someone and they wave at me, I want to turn the truck around and chase them to apologise.

We don’t really seem to be eating on this trip, or stopping at all except for fuel and an occasional wee break. Melina is an ironwoman – she competes in ironman events at a truly elite, world-class level, and can function perfectly well apparently without food or sleep. She just rolls on, being calm and capable.

I, on the other hand, am hungry, and take to sprinting into roadhouses and begging them to make me a bacon sandwich before she finishes pumping the fuel and going to the loo. I snap a couple of pics on the iphone then rush back to the car where the kids are dutifully strapped in and ready to go.

Somewhere in western New South Wales we are listening to the ABC and the host asks for camping tips. Few people know more in this field than West, so he phones up the ABC and is swiftly on air. We hear him in the back seat and then, after a five second delay lest someone let off an F-bomb, echoing afresh from the radio, nationwide. He explains we are driving from Queensland to the Margaret River.

“That is a drive,” says the woman on the radio.

Melina phones a campsite in Broken Hill, the same one she had been in with Heath a week earlier. “I remember you,” says the woman at the campsite. “You were here with your husband.” It occurs to us that it is going to look a bit odd when she rolls up a week later with a completely different bloke. “Perhaps you’d better stay in the car,” Melina says when we arrive.

As we leave the town of Cobar towards Broken Hill the farms recede to redder scrubby land and occasional bleached white trunks bereft of foliage. Stuff out here is all about surviving, including the people, most especially in the settlement of Willecania, with its Safety Home Policy signs and broken windows.

West’s name is proving tricky, in a Who’s on Third Base sort of a way.

“Are we going south, west?”

“Southwest?”

“No, West, are we going south?”

“No. West.”

“West?”

“Yes?”

Broken Hill is surprisingly pleasant and civilized. As we arrive at the caravan park some way east of the town, we are given a flyer for a “Broken Heel” drag cabaret performance. Broken Hill has digested Priscilla Queen of the Desert and incorporated it into its local economy.

The caravan park is exceptional; in fact it bills itself as the Outback Resort, and provides a lovely porterhouse steak and peppercorn sauce alongside a fine Grenache. No roadhouse, this, though the trucks barrel by all night and the railway across the road carries trains two kilometres long grinding freight up the hill. Campers are friendly and full of advice, much of it bogus; conversation bounces with generators and roof racks and tow bars.

Having discovered that everything is going to close for Good Friday tomorrow, we head to Coles, diverting to a hilltop over the still-active mines and the railyards; old mining equipment sits photogenic beneath a sunset and a bright rising new moon.

FRIDAY

Broken Hill, NSW – Streaky Bay, South Australia

The morning is chilly. The road into Broken Hill had been a flat sparse plane but it is hillier leaving it. The railway runs parallel to the road, a pleasing set of converging lines arranging the way ahead. Finally we are in what feels like outback. Red rocks like Utah sit in the distance and we make one after another time lapse shots from the dashboard. I notice that Sailor and West are far more excited about goats than kangaroos.

Three days in, conversation is running dry.

“Mum, how do you get sliced mangos?”

“You slice a mango, darl.”

So the kids amuse themselves by perfecting their English accents, gleaned not from me (I’m too northern) but from watching Peppa Pig. “Hello poppet.” “I’m a little bit British.” By the time we finally get home we will have turned this into a routine of a plumby royal family-style accent performing Give Me a Home Among the Gum Trees.

We have crossed into South Australia, and the further into it we get, the more the surroundings shift from that elemental redness to the yellows of crops as the land turns pastoral once again. We pass charming towns with railway histories and English names like Peterborough and Wilmington. And then there’s Orroro: I’m so taken with the name that I take a snap out the window of a local shop with the town name in the hoardings. I put it on Facebook. Within hours, a friend has commented: her dad owns that very shop, as random as could be. The kids try to teach me to pronounce Orroro but we just sound like a car full of gibbons trying to communicate.

At the previous campsite a family has told us that they are really hoping they might be able to make Port Augusta in a day. We hit it before lunch and it’s not even our halfway point for the day. West has been looking forward to this since he is of the view that the BP in Port Augusta is the finest servo in Australia, though as far as I can tell it is mainly a long toilet queue, which at least gives me a chance to wolf down a Hungry Jacks burger.

We pass a huge solar-powered tower at the Sundrop farm outside Port Augusta, like a 20-storey high headlight, and then seek out the road sign at the start of the Stuart Highway, filled with four-digit distance markers. Nearby we find a secret Caltex known only to triple-car road trains.

Finally we reach Streaky Bay and a new ocean, the Southern. Here, by chance, two sets of Melina’s aunts and uncles are caravanning.

I have always thought of West Australians as turbocharged, free range Australians, and here they have transplanted their lifestyle to a South Australian campsite. I have never seen so much paraphernalia wedged onto a single campsite plot. On her Uncle Roy’s site, once we’ve moved in, there is a caravan like an oil tanker with an awning to match, Roy’s immense Ford truck which makes our Land Cruiser look like a Mini, all sleek black and with a chrome exhaust like the funnels of the Titanic pointing straight up in the air, and two boats, plus our Land Cruiser. Melina reverse parks into the tiny gap like a boss, all her uncles watching.

We have a pleasant evening with her family, and I get a tour of another uncle’s caravan, within which one could reasonably launch a nightclub. Then we sit down to fresh whiting, caught that day, cooked in a deep fat fryer that Roy has, naturally, brought along.

The talk is West Australian: of weather fronts and torque and kilometres by the thousand, of fresh fish and roo bars, tyre pressure and fishing permits and the quality of boat ramps. They are generous and outdoorsy and confident and funny, and remind me of the evils the British have brought to Australia, among them cats, foxes, rabbits, starlings, toads, camels, pigeons and absolutely anything with a hoof. I have a lot to answer for.

In the night my swag collapses and I wake with my face buried in a soft coffin, scrabbling for the zips.

SATURDAY: Streaky Bay, SA – somewhere near Madura, WA

The day begins with an established routine of losing my sunglasses and wrestling my swag back into its bag, the best exercise I get these days. I’m incapable of doing it without West. There is a knack and I don’t have it. I always have an overspill of swag seeping over the top of my bag.

Today is Nullarbor day!

For years I have had a fascination with this place. The Nullarbor is famously, fabulously bleak. By reputation it is a thousand kilometres of treeless nothing, exposed to the Southern Ocean, flat and straight. When I first met the woman who would become my wife – one of the first Australians I had had much exposure to, and therefore highly exotic – I remember her referring to some guests of a flatmate as “dull as the Nullarbor.” It stuck. I always wanted to savour that dullness.

But the problem with the Nullarbor, I conclude, is that it just won’t start. A hundred kilometres driving in the morning only gets us as far as Ceduna, which apparently isn’t yet the Nullarbor. So we do another 200, and it still isn’t the Nullarbor. These distances are just obscene. The kilometres accrue on the dashboard like the altitude reading in metres on a plane.

For days we have been hearing about a weather front heading our way and we get it full in the face on our way west. Maybe it’s the rain, maybe the isolation, but both the traffic and the wildlife become more sparse. We haven’t seen roadkill for miles.

We reach the Nundroo roadhouse. Apparently that’s not really the Nullarbor either, but it’s starting to look the part, bleak and rugged in the middle of nowhere, with a wombat in sunglasses on its signage. This, I later learn, is because Nundroo has the largest population of Southern Hairy Nosed Wombats in Australia, which makes a mockery of my belief that there’s sod-all here. There are two and a half million of them in the area, which is a hell of a lot better than the Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat, whose numbers are down to a hundred or so. You can learn a lot about wombats when you spend five days in a car.

The best sign that this might actually be the proper Nullarbor is that we have started to see signs for the Nullarbor Links golf course, the world’s longest course – 1,400 kilometres long, to be precise. The idea of this is that there is one hole per town between Kalgoorlie in Western Australia and Ceduna in South Australia, including one apiece at most of the roadhouses on the way across. Here at Nundroo, the hole is called Wombat Hole. Our next one will be Dingo’s Den at the town of Nullarbor, then Border Kangaroo as we enter Western Australia and Nullarbor Nymth at Eucla Beach.

Time zones have become confusing. On the face of it, it is simple enough: New South Wales and Victoria on one time zone, South Australia on another, Western Australia another still, and Queensland’s doesn’t move for daylight saving so is sometimes like New South Wales and sometimes not. But it’s more complicated than that. Broken Hill, it turns out, has a time zone half an hour behind the rest of New South Wales. We think there is another 45 minute shift halfway across South Australia but nobody has any idea where. There will be another shift in WA. We have been so excited about the prospect of gaining an hour and a half through the day that we waste exactly an hour and a half by failing to get started in the morning.

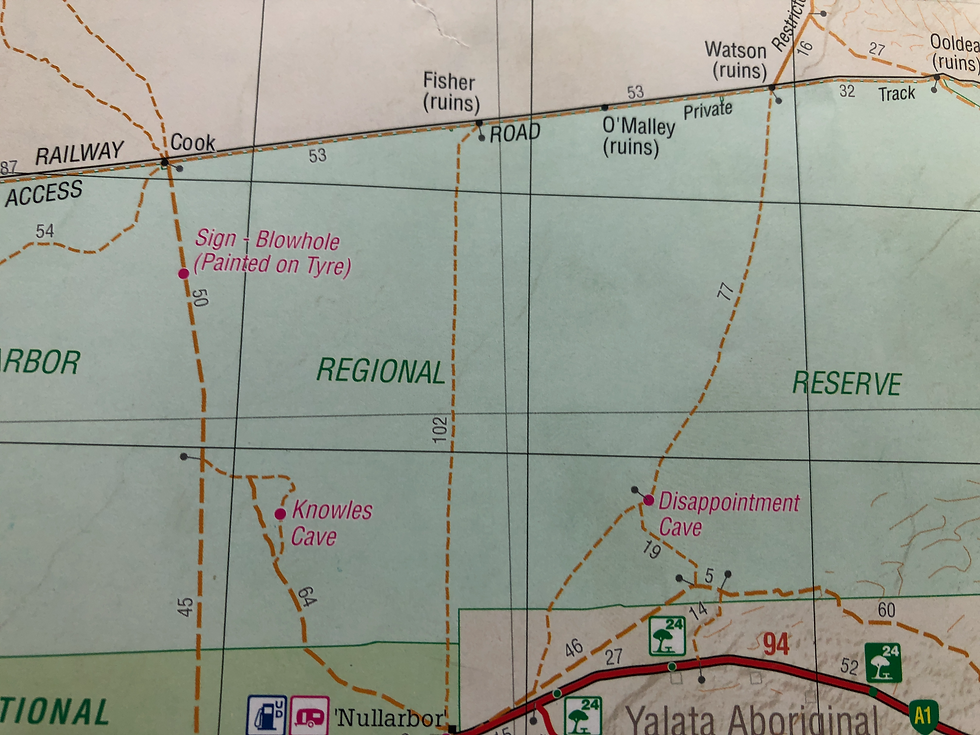

As we get more remote the maps strain for relevance. One sparsely populated page has a

marker for “Disappointment Cave” and – my favourite – “Sign: blowhole (painted on tyre)”.

Another thing maps are struggling with is what to call the pages of a road atlas in which it must deal with states that have points of the compass in their names. Right now we are on a page called Central-West South Australia. When we get onto the next page – always a cause for celebration – we will be on Southeast Western Australia. After that comes Central West Western Australia.

Hanes somehow gets me in a moment of reception and tells me Quinn wants a Travacalm before taking a drive for half an hour to a karting track in Kranji. Meanwhile, here in Australia, we have reached the point now where 100 kilometres is round the corner and I would think nothing of driving it in order to get to a shop.

The Nullarbor is bleak and treeless at the best of times but in the rain it is truly awful. When we reach the Nullarbor roadhouse – undeniably now very much on the Nullarbor – rain puddles deep outside next to the signs warning of kangaroos, emus and wild camels. I am forced to buy a Nullarbor Roadhouse Hoodie. We compare notes with fellow travelers from the other direction who report it equally dismal. A shrub is a cause for comment. Nobody is waving anymore.

The temperature falls as we approach the Great Australian Bight. Everything is Great in this country – the Great Barrier Reef, the Great Dividing Range, the Great Western Highway – and you can never really say it’s an exaggeration. When we finally stop at a look out and see the bight, rugged and bitten, where the foaming waves of the Southern Ocean crash in to eat the gutted coast, it is great. No other word would do.

Eventually the rain lifts and the Bight unfurls under a scrambled, corrugated sky. The sky is always worth comment here, because not much of the ground is. In the course of the day it goes from sullen, low and dense, borderline Mancunian, to rolling and turbulent, then violent pointing streaks amid a blueing canopy and finally, unexpectedly, brilliant azure, though it doesn’t last.

We enter Western Australia through a most polite quarantine station under the shadow of a massive kangaroo sculpture, and enter still deeper confusion about what time it is. 30 kilometres west of Madura we decide we’d better stop because the kangaroos have no better an idea than us of whether it is 4pm or 5.30 and are leaping into the road with extravagant stupidity. Their numbers, dead in the road, are mounting again; one stretch of the Eyre Highway looks like a serial killer got loose in a Kubrick movie.

We pull in to what is by no stretch of definition a campsite, lacking toilets or water or anything else, and is in fact really a muddy car park, but we camp here anyway, calling it free camping.

Instantly West is at work, finding firewood, then building a fire pit with stones, then making a fire, then making damper with his bare hands. It cooks in a bush oven he has brought along and is delicious, though he is hard on his own handiwork, and immediately sets to building a makeshift verandah to shield his swag from the rain, which has returned with a vengeance.

A campfire invokes stories, and I ask Melina about her old days sailing a tall ship across the Pacific, and how she met Hanes, and Heath. There is no phone reception, which is of varying drama to each of us, chiefly me, because I can’t follow the football.

Sunday: Near Madura, WA – Raventhorpe, WA

Easter Sunday, and as I emerge from my swag, there is a chocolate easter rabbit waiting outside in the wet red clay. When West gets up, there’s a whole Easter egg hunt arranged for him in the spinifex trees.

As usual nobody has any idea what time it is. Between us, four phones and a car come up with various 45 minute deviations. We know what time it is in Western Australia, and we are in Western Australia, but that doesn’t mean the time is right. We choose to believe we’re on the road before seven. That’s got to be right somewhere.

At the Cocklebiddie roadhouse, purveyor of fine bacon sandwiches, Melina gives me the wheel, because there’s a bit she thinks I should drive. It is a 145 kilometre stretch of road without a bend, the longest totally straight road in Australia, maybe the world.

The road becomes hypnotic, which is not ideal when looking out for stupid death-wish animals all the time. Eventually it seems slavish, this relentless following, a track with no choice, a rail to which you are attached and guided, unable to get off. The relationship with it becomes blind and dumb, a simple loyalty, with a chocolate rabbit melting on the dashboard, facing forward like the Spirit of Ecstasy on a Rolls Royce.

We are approaching Norseman, which many think of as the end of a transit of the Nullarbor, but it just doesn’t seem to get any closer. It begins to assume Biblical properties, as if one might expect a religious conversion on the way.

At one point we realise with some alarm that we are five days into a road trip across Australia without having played You’re the Voice by John Farnham. This unfathomable oversight is swiftly corrected. A VW campervan comes the other way with an apparently noble message on its front, until you say it out loud: Phuqem Hall.

Norseman finally and unspectacularly arrives. Here, the road splits: go north for the old mining towns like Kalgoorlie, south for the ocean and Esperance. We turn south.

It’s another straight-as-a-die road, sometimes among wheat, sometimes salt flats. We pass through salmon gums, named for their colour, and on one occasion a long forest of dead trees after what must have been a roiling, sprawling fire. It is a reminder that the apex predator here is fire. But even here there are signs of rebirth, green shrubs sprouting amid the white skeletons of the trees. I think back to a trip to Kakadu where an Aboriginal guide described the many different types of fires, their intensity, duration, colour, and how each had served different deliberate purposes in their society. What sort of fire was this?

By Esperance, back on the Southern Ocean, cabin fever is setting in. Esperance is a bit disappointing, shrouded in cloud and mainly closed for Easter. And so we press on, always on, to Ravensthorpe, a fifth consecutive 900km day of 10 hours on the road.

Two more hours take us to Ravensthorpe and a slightly dodgy campsite with a family that has taken over the only legal fire. We head to the local pub for dinner and a game of Uno. There are pictures of the pub’s long frontier history in black and white and sepia on the walls; I can’t see much of an identifiable difference to today.

DAY SIX: Ravensthorpe, WA – Busselton, WA

We get up for a ceremonial final rolling up of the swag. West fastens everything methodically to the roof as he has every day and we are on our way.

Today is to be what Melina calls a half day, which is to say, 515km and a driving time Google Maps estimates at five and a half hours if there’s no traffic (a dim hope on this, Easter Monday). Still, there is a going home feeling, that the big distances are behind us.

By now the topography is recognizably South Western Australian: undulating, light colours, wheat, big skies, the occasional brooding orange of a stand of salmon gums.

Driving this morning three kangaroos jump in front of the car, each the size of a man. This time I hold steady, and avoid all three. I feel like I have graduated. Then unfortunately I kill a rainbow lorikeet or two.

Near the town of Gnowangerup, we visit a firm owned by friends of Melina. They are impressive and capable and run 20,000 acres of sheep and wheat. I could never do what they do. I could never accurately pronounce Gnowangerup either. While we talk, West, now on private land, drives the Land Cruiser around the farm. We look out the window and find him successfully reverse parking, with a boat and trailer on the back.

We hit the road one last time, twice passing a vast agricultural machine on a tractor; West chats with the accompanying drivers on the CB.

Australia just will not end. The southwest rolls out languidly and no amount of driving puts a dent in it. But gradually the distance signs between the towns drop from triple to double figures, and Google Maps starts winding down the time remaining from days to hours. You play games with numbers, divide them by 50s and 10s, try to round them to landmarks, find ways to digest the crushing distance. The trees are bushy and frequent here, and the road is dappled with their shadows. The whole region broods with fertility, with growing things.

And finally we reach Busselton, their home, and our third ocean of the week, the Indian, comes into view. West puts Give Me a Home Among the Gum Trees on to accompany our arrival. Melina drives the Land Cruiser onto their lawn. We’ve done 5,000 kilometres or thereabouts in five and a half days, which means Melina and West have done 10,000 in 10 with a gap of a few days in the middle; we’ve crossed a continent, and they’ve done it twice.

An hour or so later West launches the boat into the ocean. Happily, it floats.

Comments